An Analysis of "Mathematical Discoveries From Program Search With Large Language Models"

By: Claire Pan and Kevin Lu

Paper Link: Mathematical Discoveries From Program Search With Large Language Models

Our Implementation Link: GitHub (DS4440 Neural Networks Final Project)

Introduction

In this project, we aim to explore the applicability and extend the findings of the paper "FunSearch: Leveraging LLMs for Evolving Programs to Solve Mathematical and Combinatorial Problems." Our objective is to investigate methods to improve the algorithm's effectiveness in tackling the cap set problem, which is a challenge that were originally addressed in the paper but presents opportunities for further optimization and refinement.

Building upon the foundation laid out in the paper, our project seeks to evaluate algorithm performance on this problem and compare it against traditional heuristic methods. We hope to extend the methodology presented in the paper by exploring the impact of various parameters, such as the number of islands and iterations. Specifically, we will measure how altering these parameters affects the size of cap sets discovered.

To achieve these objectives, we have implemented the FunSearch algorithm, reproduced the experiments outlined in the paper, and extended our investigations by introducing new experiments with varying parameters. We have also developed a pipeline to collect and analyze data, enabling us to generate graphs that depict the relationship between scores and samples across different experimental setups.

By addressing these questions, we aim to not only validate the effectiveness of FunSearch in these domains, but also provide insights into the robustness and scalability of its algorithmic framework. Ultimately, our project aims to contribute to the ongoing research in evolutionary algorithms and their applications in solving complex optimization problems.

Main question: How does changing the number of islands in this genetic programming algorithm affect the evolution and success of its outputs? How do different LLMs(and thus different code mutators) affect the success of FunSearch outputs?Paper Review

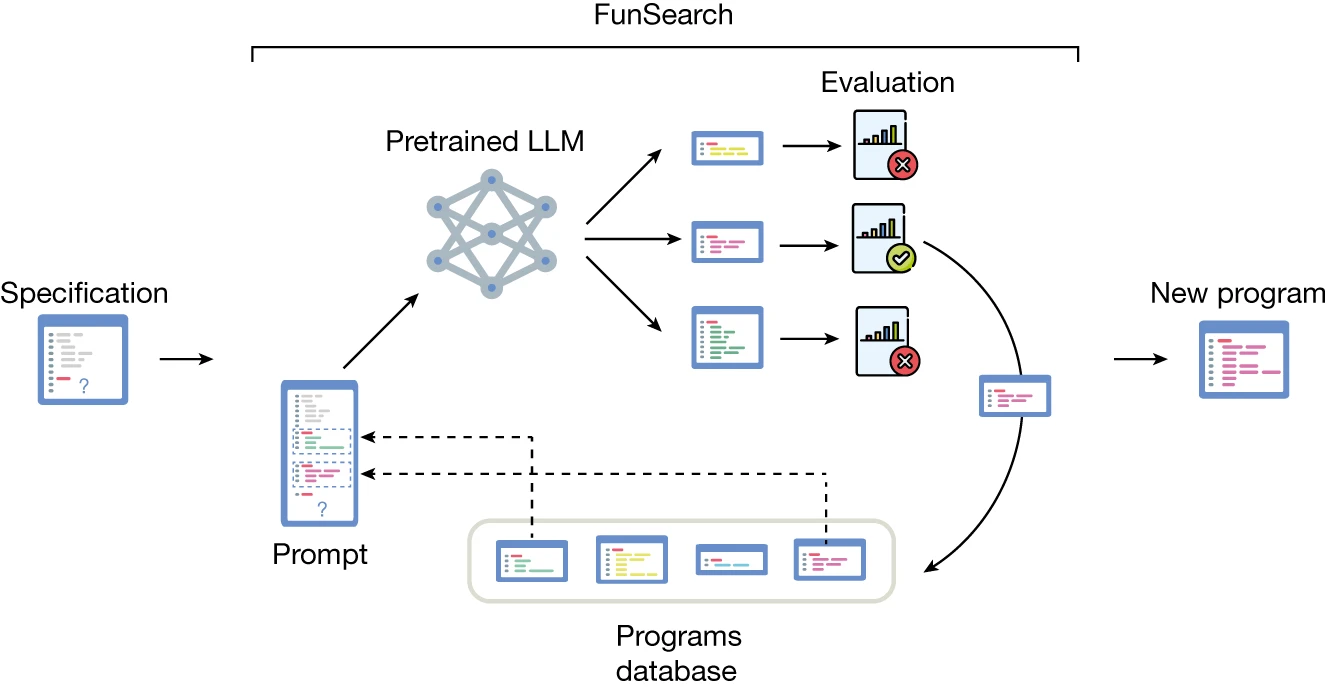

This paper introduces FunSearch, an LLM-based approach to tackling challenging mathematical and combinatorial problems. FunSearch iteratively evolves programs via suggestions from the LLM; this LLM is called Codey, and is a pretrained model that is built on top of the PaLM2 model family. Codey is a fast-inference model, meaning that is can quickly process input data and generate predictions (rather than a slower-inference, higher-quality model). Next, a distributed system comprised of three types of workers is used to store initial user-provided programs: the programs database stores and serves programs to FunSearch, the samplers query the database for prompts to guide the generation of new programs, and finally the evaluators assess the generated program performance by executing them on inputs of interest and providing feedback.

The algorithm skeleton provided by FunSearch serves as a template for program evolution and is demonstrated in this paper on two different problem domains: cap set construction and online bin packing. Researchers found that in the cap set problem, FunSearch was able to exceed traditional methods by discovering larger cap sets in higher dimensions where brute-force approaches were impractical. Similarly, in the online bin packing problem, FunSearch was able to outperform traditional heuristics by evolving more effective packing strategies. Overall, FunSearch offers scalability, flexibility, and enhanced performance over existing approaches, showcasing its potential to address a wide range of challenging optimization problems.

In our research, we chose on research FunSearch's abilities in the cap set problem, which is known as one of the best known problems in additive combinatrics. The cap set problem refers to finding the largest posible set of vectors in a finite field such that no three elements in the set can sum up to zero. As this problem has been consistently debated and investigated within mathematics, we thought it would be interesting to push the boundaries of FunSearch in finding the largest possible cap set in `n` dimensions.

In addition to its approach to tackling mathematical and combinatorial problems, FunSearch incorporates an island mechanism within its evolutionary algorithm framework. This allows for greater efficiency and effectiveness of program evolution by leveraging parallelism and diversity maintenance strategies- by partitioning the population of programs into multiple islands, FunSearch enables simultaneous exploration of different evolutionary paths, similar to conducting several smaller experiments concurrently. Since there is a periodic resetting of low-performing islands, this ensures that better evolutionary trajectories are not prematurely abandoned, which allows for continued exploration and adaptation within each island.

It is important to note that within each island, programs are clustered based on their signature, allowing for targeted sampling and selection procedures that prioritize high-scoring clusters while still preserving diversity within islands. A signature refers to the program's performance score on each test case, such as the size of a cap set for each input value. Thus, programs that perform similarly across different inputs are grouped togehter into clusters. This clustering and selection mechanism helps the FunSearch algorithm navigate the program space more effectively, avoiding stagnation in local minima. This island mechanism enhances the scalability, adaptability, and robustness of FunSearch, thus, we hope to extend on this research by applying FunSearch to the cap set problem and evaluating the scores.

Method

In order to implement FunSearch, we first connected to OpenAI 3.5 Turbo via their API and registered for a key with $5 worth of credits. For generating capset solutions, LLMs are prompted in the form of:

This capset specification provides a skeleton of code that the LLM with evolve over many iterations. It defines a baseline greedy algorithm for generating capsets(initially of size 2048 for dimension 11) The returned code is then run in a Docker sandbox(developed by jonppe on Github) and the performance of the solution evaluated. This is where we extended the implementation of the original funsearch paper, by examining the # of islands as a hyperparameter upon which we can perform a search.

Starcoder

We also utilized the publicly available starcoder model on HuggingFace as part of our investigation into how different LLMs would perform on the capset task. Beyond just using the "raw" model, we also investigated if a fine-tuning approach would be change the performance at all(as well as getting an excuse to use the Northeastern HPC cluster).In order to fine-tune the starcoder model, we used the mangrul/hf-stack-v1 dataset available on Hugging Face as well as their open source starcoder model.

To further reduce the size of the model we utilized the Low Rank Adaptation Technique(LoRA):

And checked-out a P100 single GPU via Open OnDemand to run the fine-tuning Jupyter Notebook.

Experiment Setup

Increasing the number of islands also drives up computation costs and # of API calls in total - each island requires a separate API call to the LLM for each evolution iteration. In order to account for this, we limited the number of "samples" (API calls) to under 300. We ran a series of experiments on 15 island values(1-15), with each experimental result an average of 3 "runs" of evolution. In total, we made 45 full "evolutions" of programs: 3 evolutions * 15 islands = 45 total evolutions. The results in the bar graph are the average maximum performance of each # of island configurations.Findings

Our findings indicate that the number of islands in the genetic programming algorithm has a significant impact on the evolution and success of its outputs. Specifically, we observed that increasing the number of islands led to a more diverse set of programs being generated, which in turn increased the likelihood of discovering high-performing solutions. This suggests that the algorithm benefits from a higher degree of exploration in the search space, which is facilitated by the parallelism introduced by multiple islands. Below are some sample "histories" of evolutions for different island values:

Using other LLMs

Variation = sqrt(Σ(scorei - scorei+1)2 / n)

Raw Starcoder: 2917 peak, 450 variation

Fine-tuned Starcoder: 2950 peak, 100 variation

ChatGPT-3.5: 4096 peak, 300 variation

While variation is not a perfect metric, it does give us a sense of how "stuck" the model is in a local minima. The fine-tuned model, while having a higher peak score, is much more likely to get stuck in a local minima than the raw model. This is likely due to the fine-tuning process, which may have overfit the model to the prompt data. However, ChatGPT performed significantly better overall, likely due to the true "correctness" of its code. In this game of nature, ChatGPT3.5 shows the greatest success as a evolutionary engine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study looks into the application of the FunSearch algorithm in tackling the cap set problem, and has provided valuable insights into the dynamics of program evolution. Through different experimentation, we have demonstrated the significant impact of adjusting the number of islands in the genetic programming algorithm, researching the balance between exploration and computational efficiency. Our overall findings suggest that a higher number of islands (optimally 10 islands) creates greater diversity among generated programs, leading to the discovery of more effective solutions. However, this enhancement comes at the cost of increased computational resources. Looking ahead, our research begins to lay some framework for further exploration into refining evolutionary algorithms and their practical applications, and helps future researchers better understand the ways in which the FunSearch algorithm can be better implemented and refined for greater efficiency and accuracy.References

[1] Romera-Paredes, B., Barekatain, M., Novikov, A. et al. Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models. Nature 625, 468 - 475 (2024).

[2] Mouret, J.-B. Large language models help computer programs to evolve. Nature 625, 452 - 453 (2024).

Team Members

1. Kevin Lu (lu.kev@northeastern.edu)

2. Claire Pan (pan.cl@northeastern.edu)